We have already discussed the Vanishing Self when we dealt with David Hume. So, what more is there to say? Well, there is always the Austrian dimension again, including the man who thought that the no-longer-existing-Self, like ancient Gaul, was divided into three parts:

(1) The Ego, which handles most of the publicity (well, it would, wouldn’t it?)

(2) The Super-Ego, don’t ask. I said, don’t.

Okay, so let me guess … The Super-Duper-Ego which ensures that everything one says is charged with real meaning, and not just the uninterpreted noise that John Searle talked about when he discussed his infamous Chinese Room Argument, yes?

We-ell, not quite. But close.

Incidentally, ‘Searle’ rhymes with ‘Earl’, as in ‘Earl Grey Tea’. The German words are a bit peculiar, but a useful mnemonic is the little ditty much beloved by amateur philosophers of my parents’ generation, namely: Nietzsche is peachy, but Freud is enjoyed. I just thought you ought to know this.

Anyway, a little light music will not come amiss. A Viennese waltz might be appropriate, but I prefer to remember punting on the Cherwell during the long hot summer of 1976. The first rain (in late August) came on the precise day when John and Elizabeth (two of the people with whom I was sharing digs at the time) were married. The wedding reception was not ruined, by the way.

So are you like one of those weird multiple-personality people whose body gets to be controlled by various different personas at different times? Like Dr Jekyll (the ego) and Mr Hyde (the super-duper-ego), but with some sort of intermediate super-ego that keeps – and very wisely so – in the background most of the time?

Well, it rather depends on whom you ask. For example, Plato‘s threesome (as expounded in the Phaedrus) consists of a charioteer with two horses whose colours reflect his sensitive attitude towards matters of ethnicity. The white horse is the voice of Reason that would, if left to his own devices, make a beeline for the world of Forms, a realm outside the world of space and time altogether. The black horse (of uncertain gender) would lead us all astray and climb a pleasure gradient towards whatever it is that lies at the summit of that particular mountain. The charioteer has the unenviable task of trying to keep everything in one piece: such is the role of a committee chair.

Something alone these lines was developed at greater length in the Republic, where the chief task was to defeat in argument a rather strange character called Thrasymachus.

Even Hume was not above this sort of story-telling, though for him, the chief battle within his non-existent self was fought between faculties rather than agents, notably Reason and the Passions. He declared that not only was Reason the slave of the Passions, and that it was not contrary to Reason to prefer the destruction of the world to the moving of his little finger …

… but, in order to annoy the Platonists, he also insisted that this was also just the way things ought to be. He did not quite explain how this particular ought derived from an is.

It might be thought that hard-boiled materialists – or physicalists, as they prefer now to be called – will have none of this sort of play-acting, but that is not true. Artificial intelligence (AI) models of human functioning make frequent use of homunculi, who are sort of invisible sub-humans who do all the routine work.

Exactly what it is like to be a homunculus is a question that worries only the most sensitive (and probably most confused) sort of physicalist. However, since they have no independent existence, there is no obvious reason to want to exterminate them, something that Nietzsche probably realized, even if some of his more famous admirers did not.

A more advanced sort of homunculus is called a numskull, and there are relatively few of them per person. Their mode of operation is, however, a little hard to grasp. Readers of the Beano (a specialist literary outlet) debate at length about these matters.

Critics of numskull theory tend to focus on two main lines of objection, empirical and philosophical. The former centres on the fact that numskulls seldom appear on X-ray slides, and are suspiciously adept at avoiding surgeons’ scalpels. The latter concerns the more theoretical problem of whether their activities are genuinely explanatory. One rather direct line of argument centres on the question of who actually controls the numskulls? Do they have second-order numskulls inside their heads? If so, the prospect of an infinite regress beckons.

Does this matter, I hear someone ask plaintively? After all, we have learnt from the great logician, Augustus de Morgan, that:

Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

A more developed picture is defended by Dr Seuss, though the fact that each cat’s hat is required to contain a miniature version of the cat-hat whole is left strangely unexplored.

Perhaps the infinity is resolved by considering the totality as a single completed entity. However, I have already spoken of the transfinite hierarchy elsewhere, so will not develop this idea, or trouble you about the difference between a limit ordinal and a successor ordinal.

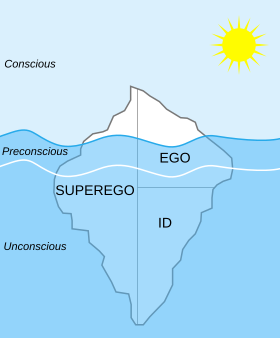

Anyway, back to Freud. Now, I have to say that my original depiction of his tripartite division of the soul might have been a little misleading. The Ego is indeed below the unmentionable Super-Ego, but the more interesting Super-Duper-Ego is actually below the former, not above the latter in the general hierarchy of things.

Moreover, in keeping with the Spartan nature of the German language, we need a briefer label, preferably something which rhymes with ‘Sid’. And, sure enough, following the traditions of the city of waltzes and Sachertorte, we get the following: the Id is a highly sensitive – indeed, sensual – soul, and the preferred pronoun is it/its.

The following musical number could probably be set to a 3/4 tempo if you really, really tried.

So, how does Freud explain human mental functioning? The gist of it is that the Id pursues animal pleasures without any real consciousness of what it is doing, whereas the Superego has a weird obsession with moral perfection, with always doing the right thing all the time. The Ego, who, as mentioned, is the mouthpiece of the whole person, tries to steer a middle ground between two extremes, neither of which has much chance of success if left to their own devices.

So far, so only moderately interesting. We all recognize a tension between our sense of duty and our basic appetites. Neither can really survive without the other: duty needs appetite, otherwise there is nothing for our moral sense to work on; and appetite needs to be tempered by duty since we need other people in order to thrive, as Freud notes in his Civilization and its Discontents. Where matters become more original is in the actual dynamics of the interactions between these forces – for we are also given the independent tripartite division of the psyche into the conscious, the preconscious and the unconscious. This gives us a complex two-dimensional structure, one with great explanatory potential.

How does this work? Well, much of what we say and do is odd, i.e., does not have an obvious explanation, but evidently needs one. If we can construct a story that makes the phenomenon in question intelligible, then so much the better.

Ideally, this story will yield predictions that are falsifiable, in the sense that not every conceivable outcome is consistent with the story. This, alas, is a weak point in the theory, and has led many to conclude (following Sir Karl Popper) that Freud was a pseudoscientist.

However, even if the above charge were to stick, it would not conclude the matter, for a Freudian could always abandon the claim to be scientific, and claim instead that Freudianism has some other status (say, a purely philosophical or metaphysical one).

Moreover, not all good explanations yield falsifiable predictions. The most obvious counter-examples here are historical explanations, and if we side with Collingwood (discussed elsewhere) against the German-American philosopher of science, Carl Hempel, then we get space for a very useful synergy. This is because the psychoanalyst must re-enact and/or empathize with some of the mental states of her patient (albeit in a professionally detached manner) in a way made very clear by Collingwood in his general account of how to explain human behaviour. This is essential if we are to understand people as people and not just as physical bodies.

But does human mental functioning really require such elaborate two-dimensional tripartite modelling? Well, arguably, yes. Ostensibly irrational behaviour, such as the notorious Freudian slip (or parapraxis, to give it its technical name) that betrays our innermost thoughts and desires, can be rendered intelligible if we suppose that the Ego is constantly influenced by an Id that seems to be more interested in sex (and, occasionally, killing enemies) than in polite conversation.

Also, our dreams, including our daydreams and inner muses, have a strange, free-floating quality that seems to make sense at the time, but cannot easily be understood when put under the spotlight. If we postulate influences from the unconscious, a kind of sense can be made, as is illustrated in this well-known film extract:

What about psychoanalysis? The dissection of the human psyche according to Freudian theory is not meant to have a purely intellectual value. On the contrary, it is primarily meant to have a therapeutic value, in particular as a way of treating the psychoneuroses (the more serious psychoses, by contrast, are deemed to be largely resistant).

Does current medical opinion support this optimism? It depends a bit on whom you ask, of course, but in the UK, psychoanalysis is generally thought to be of limited value. It is not that talking therapies as such are dismissed as ineffective – on the contrary, it is recognized that chemotherapy on its own is of limited value (even with the newer tablets). Rather, it is generally (though not universally) felt that there are better styles of psychotherapy (cognitive-analytical, cognitive-behavioural, and so forth).

Freud is still studied, of course, but for some time now, it is striking that if you find yourself in a seminar room talking about Freud, then it is more likely that you are a humanities student than a medical one. It is in literary criticism, and not clinical medicine, that Freud is most valued, and this is itself something worth examining.

I discussed at some length, in the ur-article, the view that all meanings are formed through metaphor. This thesis, which we associate primarily with Nietzsche, ensures that meaning is not a simple, one-dimensional flow from one word or phrase to the next, but has layers. Below the first, the dead metaphor comes alive, and a more literal meaning is perceived, both earthier and more vivid. Sometimes, this leads to trouble, and even the elementary rules of logic seem to be violated. Let me illustrate.

Eloise, our ten year old enfant terrible, has just been told to behave herself while her mother goes into town for her fortnightly visit to the hairdresser. She has been told repeatedly that ‘Mummy has eyes in the back of her head’, and still half-believes it. After all, when she was three, this hypothesis provided the most obvious explanation for what Mummy seemed to know about her surreptitious attempts to get to the biscuit tin or to annoy the local hamster. She also knows (because she has overheard this on many occasions) that Mummy rather likes the young trainee hairdresser with whom she can have a frank and relaxed conversation about being a parent in this day and age. She perhaps also knows that Mummy does not like wearing either glasses or contact lenses, hates going for her annual visit to the optician (with its horrid pressure-measuring machine that blows cold air into the eye while she has to rest her chin on something or other), and has no desire to be told that her vision is in any way abnormal.

Now, logicians sometimes talk of the agglomeration principle, namely that if you are given two independent pieces of information, then you may join them up to form a single whole. For example, from ‘Snow is white’ and ‘Grass is green’, you are allowed to conclude the complex sentence ‘Snow is white and grass is green’. However, Eloise, despite her obvious talent for trouble, has not yet drawn the obvious conclusion, namely that the trainee has left her place of employment in hysterics, and that Mummy has been blacklisted by every opthamologist in town.

The sad fact is that, had she read her Nietzsche more thoroughly, Eloise might well have predicted all this, and could even have explained thoroughly why her older teenage brother keeps getting nightmares after seeing That Film – the one which depicts shocking images of rocking beds and swivelling heads, I mean, of course.

Naturally, there are deeper layers of meaning as well, and even the phrase ‘back of the head’ has a metaphorical tinge that can be literalized if need be, even though there is enough consternation in the general vicinity to be getting along with.

Layers of meaning also go in the opposite direction, away from raw sensation and towards greater cultural significance. Pictorial images in particular are subject to this sort of interpretational depth, a fact which we particularly associate with Roland Barthes.

This famous magazine cover depicts a young French soldier saluting. However, at a deeper level, it signifies a more complex sociological and anthropological story about the relationship between what it is to be French, black, militarily obedient, and so forth. Each layer of meaning is deeper than the most literal original (which does not talk of depiction at all, but merely describes the chemical composition of the surface molecules of the paper itself).

So, the answer to the question, ‘What do you actually see when you look at the magazine cover?’, is necessarily complex, and involves issues more frequently discussed by philosophers at ease with concepts such as hermeneutics, exegesis and phenomenology, than by the Anglophone mainstream when they discuss the philosophy of perception.

Analytical philosophers tend to be impatient with intense psychological description, an impatience that often borders on contempt. Thus Jean-Paul Sartre has a wonderful image of a voyeur/eavesdropper whose ear is pressed to the door whilst looking through the keyhole, utterly absorbed in what he is doing – and who then suddenly becomes aware that he himself is being watched. Do they (the analytical philosophers) examine the sort of Gestalt switch involved, similar (perhaps) to that which involves the metamorphosis of Jastrow’s duck into a rabbit? No, actually, they don’t. Instead, with that rude literalness beloved of the Anglo-Saxon, they merely observe that not even French skulls are so shaped that they permit one to look through a keyhole whilst one’s ear is simultaneously pressed against the door.

Post-structuralists get similar treatment, and it is sometimes thought that a short poem will summarize adequately several metres of dense prose, as the following ditty illustrates:

D’ya wanna know the creeda/Jacques Derrida/There ain’t no reada/There ain’t no wrider/Eider

Anglos know that the emphasis in the word ‘Derrida‘ is actually on the first syllable, not the second, but nevertheless still regard him with a certain suspicion. They quite like Édith Piaf, however, as the following petite chanson illustrates:

The French like their wordplay, and their writings are full of puns, malapropisms, sound-alikes, and so forth, unlike the Anglos who prefer a terse and directly argumentative style. However, we have already experimented, in the infinitely respectable ur-article, with a playful style which conveys a powerful illusion that the reader is in direct telepathic communication with the author. The author seems to know what the reader is thinking, and the reader has the eerie sensation that she knew all along what was going to be said.

How so? Well, a cheap trick is to inform your audience, having set the scene with various spooky gestures, that you know exactly what they are thinking about this moment. Inform them, for example, that they are now thinking about purple giraffes. They will then be amazed to find that you have guessed correctly, a feat all the more remarkable in that it is such an unusual and unpredictable thought.

(This is in striking contrast to the rather feeble skills of Marvo the Mentalist. He can read the mind of his cat – who has been sitting impatiently by the food bowl for some time now – and can telepathically observe that she is hungry, to everyone’s general amazement. Well, fancy that.)

Is the purple-giraffe trick a case of telepathy? In the absence of a precise definition, I think we should not rule this suggestion out. After all, young telepaths must start somewhere, and members of the next generation of Midwich Cuckoos (remember them?) may well feel impelled to address their mothers by informing them that they wish to be taken to the zoo right now, and command them to think of purple giraffes or else …

Can small children command their mothers in that way? Anyone who has ever heard of upward bullying must take the possibility seriously.

As far as Homo sapiens is concerned, the problem is that reading a text is a complex matter. I am not thinking so much of hermeneutics as the phenomenon studied in psycholinguistics by means of an eye-tracker among other things. In ordinary reading, we do not look at each word consecutively but glance about the page, and information is gleaned in a complex manner. Moreover, it is gathered, stored, processed and finally used in real, non-infinitesimal time, and we are not fully conscious of the earlier stages of the processing (and, furthermore, the ordinary order of business can be altered if one is sufficiently excited).

The upshot is that, given a certain literary finesse (combined with bit of low cunning), some impressive psychological illusions can be created, including that of telepathy.

So does this mean that I am admitting fraud, and that my claim to be bringing telepathy to the masses is a kind of stylistic conceit after all? Once again, I do not think that we should rush to judgement on this matter until we have a precise definition, and we do not have one. We do not understand enough about mental concepts.

So what more do we need to know? Well, again, the problem of literal versus metaphorical meaning is primary. The ur-article teases the reader about the philosophy of language, in particular with Wittgenstein’s view that meaning is constituted by a kind of continuity in the following of linguistic rules. Yet the sceptical implications drawn by Saul Kripke in his interpretation of him (so-called Kripkenstein) are devastating. It seems as if each new application of a word requires a kind of leap in the dark (there are no pre-existing rails to guide us).

Now, when a word is first used metaphorically, its use changes. But what is the difference between following the same old rule, and following a changed version? Without the pre-existing rails, the contrast becomes deeply mysterious, and we are thus led to the view that all meaning is metaphor in a very strong sense – indeed, far stronger than the more modest proposal, and one which is deeply implausible, since the whole distinction between the literal and the metaphorical (on which the very concept of the metaphorical depends) is destroyed.

A theory which destroys its own foundations cannot stand, as Abraham Lincoln never quite said. Not even Wittgenstein’s. And we can see why the French like putting much of their writing under erasure. Perhaps a minimal sort of plainsong might help here.

I think this is probably enough to be getting along with.