I hate to repeat myself, still less to repeat the words of someone else discussed in the previous post, A New Treatise of Human Nature (from ‘On Personal Identity’, in case you were wondering), but some passages are so famous (and so weird) that they need to be constantly kept in mind, lest they disappear into a mental black hole of forgetfulness (to coin a phrase).

… For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception.

A little while later, Hume continues …

But setting aside some metaphysicians … I may venture to affirm of the rest of mankind, that they are nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement. Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying our perceptions. Our thought is still more variable than our sight; and all our other senses and faculties contribute to this change; nor is there any single power of the soul, which remains unalterably the same, perhaps for one moment. The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations.

As often happens with great philosophers, the prevailing view is that Hume is both obviously right (this permanent self is just not there to be seen, heard, felt, touched, tasted or smelt alongside its constituent perceptions), and obviously wrong (just who is he talking about when he compares himself to the rest of mankind?).

This is also a view easily understood and grasped by all, not just those trained in academic philosophy.

If we want to aim at truth – if we should like our beliefs to be accurate – then we must evidently adapt our ideas so that they more closely resemble the things in the world outside of us. Notwithstanding our earlier puzzles about Spinoza and Berkeley, this seems just obviously right.

So how do we do this?

The problem is that the flow of our ideas cannot be nailed down in the laboratory, frozen into temporary immobility and then re-examined – either under the microscope or in a test-tube (depending on which you prefer, physics or chemistry). The thing about flows is that they flow: if they ceased to flow, they would cease to exist altogether.

But do we really have to suppose that our inner lives – our inner narratives (if you prefer) – resemble some sort of stream of consciousness novel, a genre we tend to associate with James Joyce (whom Ryle greatly admired, and often mentioned in The Concept of Mind, by the way)?

Does Ulysses really have to look like this?

After all, Joyce is pretty hard going, and his final masterpiece Finnegans Wake totally unreadable – and deliberately so.

Some have concluded from these sort of considerations that thought cannot be studied scientifically. For example, Ryle’s predecessor in the Waynflete Chair of Metaphysical Philosophy at the University of Oxford (the oldest and arguably the most prestigious Professorship in the world) was Collingwood, famous as both an archaeologist of Roman Britain, an aesthetician and as a philosopher of history.

(By the way, the philosophy of history is quite different from the history of philosophy, just as the administration of policy is different from the policy of administration – do keep up! Oh, all right then, you can have another TV clip, seeing as it’s you …)

Okay, okay, so what did Collingwood think that was so relevant, I hear you ask with just a hint of impatience? Well, in the Epilegomenon (don’t ask) to his The Idea of History, he completely trashes the very idea of psychology, considered as the science of the mind.

It is not that he was against the original idea of science (Latin = scientia) in the broad sense of an organized body of knowledge (it is in this sense that the law is sometimes referred to a science, even though Law Schools tend to be grouped under the Arts not the Sciences at most universities).

What he was against was the view that the natural sciences, most particularly physics, should be the model for the study of human thought and action. Human beings should not be thought of as mere things.

Aha, I hear you say, some serious metaphysics at last! Did Collingwood therefore say something that Ryle might have disagreed with? Given that human bodies can certainly be studied by physicists and chemists without impropriety, did Collingwood therefore believe in an non-physical soul wholly beyond the ken of any mechanistic philosophy?

Well, no, actually. For a start, Collingwood has often been accused of being a relativist about truth, thinking (as he did) that Newtonian physics was part of the absolute presuppositions of the 18th Century, but had no universal validity.

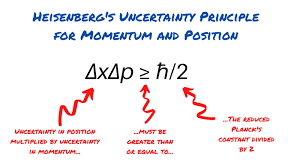

What he (Collingwood) implied (and he made this explicit) is that Kant’s attempted proof of the principle that every (observable) event has to have a cause (something that 20th Century philosophers of physics, mindful of the indeterministic aspects of quantum mechanics, tend to sneer at knowingly) is presented as something that was only meant to have local validity, and that the behaviour of radium atoms when they decay into radon atoms is just outside Kant’s world.

The thought of the 20th Century has its own, rather different absolute presuppositions, so intellectual peace can be maintained, and nobody need be offended unduly.

So, does this mean that the particles that compose everyone and everything started to behave differently when people’s absolute presuppositions about them changed, we ask incredulously? If so, why did they (the particles) bother?

Alas, apart from the fact that Collingwood despised his fellow professors whom he called minute realists (in this context, the word ‘minute’ sounds like ‘my newt’, not ‘minnit, as in “just a minnit”‘, by the way) we are unsure just what his considered response was. His colleagues concluded that he was really just an archaeologist who had wandered into philosophy whilst under a misapprehension.

Nowadays, we talk of Freshman Relativism, the view espoused by indignant first-year undergraduates who say emphatically, ‘Well, it was true for them!’, when they are informed that the mediaeval peasants’ view that the Earth is flat was just plain false.

(The problem with this sort of relativism is that it is not at all clear what it even means to talk of truth for a person or group of people. What make it a kind of truth?)

Ah yes, I was talking about Collingwood’ views about history.

Well, to cut a long story short, he thought that the way to explain why (for example) Caesar crossed the Rubicon was not to search for a universal law (what Hume had earlier called a constant conjunction) connecting the behaviour of dictators and rivers – even when the behaviour of dice is added as a complicating factor (this might be necessary, as anyone who knows what ‘alea jacta est‘ really means).

No, no additional very expensive laboratory equipment in the Psychology Department, and no additional field trips to visit a carefully sampled selection of the world’s dictators for that matter will assist us in understanding human behaviour.

As this Icelandic musician explains to us very clearly.

No, no, no! What we should instead do is re-enact in our minds the thought that underlay Caesar’s actions. We need to remember that an intelligent action is not just a piece of bodily behaviour. It has an inside as well an outside. The thought that the action embodies sort-of-causes the outer behaviour, but the relationship is more intimate than that between two distinct events (a purely mental one and a purely physical one).

Well, isn’t this just obvious? Don’t we explain the eruption of Vesuvius in 79CE as the outer expression of the boiling inner rage that the god of volcanoes naturally felt for the decadent behaviour of the good citizens of Pompeii? I mean what else do volcanologists do for a living apart from placating such gods by occasionally pouring a few virgins into craters as a nice, tasty human sacrifice? (This is meant to be sarcastic, by the way.)

Likewise, how else do you explain why dropping a small lump of metallic potassium into a glass of water causes the former to burst into a purple flame than by re-enacting the experience and asking you yourself, the experimenter, how you would behave if you were treated in that way? And what else is that mad Siberian peasant’s Periodic Table for other than to introduce some rational order and method into a world that contains just a little more than Water, Earth, Fire and Air? (No, I mean Mendeleev, not Rasputin.)

Okay, so people like Galileo and Newton discovered that better predictions could be had by doing things differently. Instead of trying to understand the world, it is better simply to focus on repeatable experiments involving precisely measurable observables and then do the math, as the Americans put it.

And if that is not enough, then improve the math (but don’t steal ideas from Leibniz – otherwise we should cease to live in the best of all possible worlds, and we don’t want that, do we?)

And since the predictions will involve the behaviour of artificially constructed things, this gives us … technology!! Well, aren’t we the lucky ones.

Now, some (e.g., B.F. Skinner, a 20th Century behaviourist) thought that we should extend this intellectual leap, and that it was time that Psychology found its Newton and thereby discover once and for all the the underlying universal laws of human behaviour.

The publicly measurable observables in behaviourist psychology are the stimuli and responses which folk psychology thought provided the causes and effects, respectively, of our inner mental states. Yes, really. Don’t mess with the folk, or else you risk a populist backlash.

Another behaviourist was the physiologist Ivan Pavlov who, as you know, trained dogs to salivate whenever they heard the dinner gong, something that many of us do quite naturally (as it happens).

The point is that, although ideas are mental and therefore don’t exist in the first place, behaviourists proved that the association of ideas does not depend on intelligible internal connections between them, but simply on artificially induced regularities. It’s called a conditioned response, by the way, and you will go into the Skinner box for a few days if you don’t believe me.

Strangely enough, Hume himself, back in the 18th Century, thought something similar. This reasoning is incredibly famous among analytical philosophers, so pay attention.

We notice firstly that like causes have like effects

(Incidentally, the word ‘like’ here is an adjective and not a mere interjection, as the hippies who may still be among you need to know.)

This sets up an association of ideas (what Skinner calls operant conditioning, though operated by the ideas themselves, not the experimenters. With me, so far?)

Now, in order to cover its tracks, the operant conditioners bribe the Imagination (a sort of evil twin of the Understanding) to trick us into thinking that there was already some sort of necessary connection between cause and effect, so that nothing looks like a coincidence any more (Spinoza, just keep quiet for once).

In short, magical or miraculous breaches of what we are pleased to call the Laws of Nature, from the Law of Gravitation (if you jump off the top of the building, there is no turning back) to Maxwell’s Laws (if you mess around with electricity and magnetism at the same time, then you set off invisible light in all directions) are perfectly possible. They just haven’t happened yet.

By the way, if you really want to annoy a physicist, tell her that Maxwell’s Laws suffer from a problem of induction – a term that was first used in this context by Auguste Comte, writing in the early 19th century. But you all knew that, didn’t you?

Because you are so clever, you may now have a very refained musical break. Don’t rattle the teacups, please.

Okay, so the physicist only looks half-annoyed. So tell her that what holds the exterior of her fancy apartment together is nothing but good quality mortar.

(Don’t call it the Cement of the Universe, as that might mean treading on the toes of the Civil Engineers, people who are at their best when they are civil. Don’t call it glue either.)

In case, the physicist looks as if she has forgotten her lines, ask her if she knows what actually sticks the bricks onto this mortar which is being used to stick the original bricks together. (No, it is not high quality meta-mortar, in case you, O Best Beloved, were wondering.)

Classical scholars, with a penchant for the irrelevant, have a tendency to talk at this point about the TMA, which stands for the Third Man Argument, something which happened to Socrates when he met a weirdo called Parmenides. The third man may have been Zeno, but nobody is quite sure …

… and if you are a Scouser comedienne who needs something to do, inquire whether there are any direct trains between Harry Lime Street and Wien Hauptbahnhof. The rest of us, however, will take a well-earned little film break.

Now that your physicist friend has been softened up a bit, inquire politely what holds any solid object together if there is no glue involved. She, with a strange light in her eyes, will almost certainly talk about the Standard Model, subatomic particle exchanges, and finally … yes, finally about gluons, which are invisible particles so little that they barely exist at all. Yes, really.

If you then want to make a successful night of it, it would be wise not to ask what sticks the top half of a gluon on to the bottom half.

Just don’t. Just find a nice restaurant instead.

************

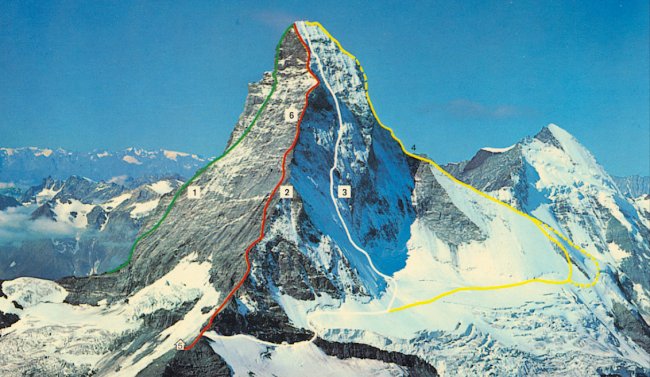

Okay, so we seemed to have reached a sort of half-way house between base camp and our summit.

The question on everybody’s lips, however, seems to be whether we really took the most direct route. If you are the sort of person who reads standard Logic Textbooks, you may be led to believe that a shorter – and therefore simpler – route was possible, but I suggest some caution here.

Mountains have a complex topography, and some forms of skilift require a constant direction but can tolerate a varying gradient, especially if you can rely on elaborate steel support structures and have a head for heights. Others, more traditional, keep firmly to the ground, cannot easily tolerate changes in gradient, but are flexible with regard to direction.

We also need to consider which route upwards requires the least effort, physical or intellectual, and there is no obvious reason why the shortest should prove to be the best.

Of course, it is easier to be wise after the event, and once one’s brilliant new train of thought has arrived and one wishes to test the credibility of its conclusion, a more succinct refashioning of the argument may be preferable than the original rather tortuous route, regardless of the accompanying spectacular scenery. (Phew!)

But remember that the ability to think creatively is different from the ability to think critically. The former is needed to produce new ideas, whereas the latter is needed to test old ones, and some people are better at one rather than the other.

Sherlock Holmes, for example, talked of deduction in a way very different from the way in which professional logicians use the word, and his inferences were surely artefacts of hindsight.

What originally led him to his solution to the crime were highly intuitive trains of ideas that could not be easily captured intellectually (after all, they happened at the same time as he was actually attempting his intellectual activity, if you follow my drift), even if the later testing of the hypothesis used only cold logic in some sense of the phrase.

Another point, seldom noticed save by experts, is that spoken English is very different from written English. An exact transcript of a lecture, for example, even one spoken by an erudite speaker, is full of grammatical solecisms and other strange quirks which linguists study for technical reasons of their own. Are we going to say that nobody actually speaks the Queen’s English? Or would we not rather say that the rules of good English are weirder than they look.

True, a thoroughly rambling account is tolerable only in the very elderly. Youngsters are expected to focus, to gather their thoughts together before proceeding, and to maintain relevance at all times. Anything else will distract, and therefore irritate the listener, and an irritated listener cannot concentrate that easily.

But suppose that we are aiming to be telepathic? Should we not try to simplify the route by which one stream of consciousness reaches out to another? As it is, both the speed and the reliability of transmission are compromised by the fact that the conventional linguistic medium requires the use of descriptive and normative rules accepted by most good English writers (with the possible exception again, of course, of James Joyce).

Of course, the Irish do things differently, and an extensive pub crawl around the streets of Dublin may lead to conversations less often heard on the other side of the Irish Sea.

It may be protested that unacceptable behaviour may still be commented on in an acceptable way, as is evidenced daily in any Magistrates’ Court.

Linguistic behaviour is likewise protected once the precise logical function of a quotational context is understood, and a careful English writer can always produce a thoroughly respectable novel which runs (along the lines of):

I am appalled, and disgusted, to say that it has come to my attention that the following lines were written by an illiterate acquaintance of mine. They are [insert the offending text]. Down with this sort of thing!

And does it matter how long the offending text is? Well, how long is a piece of string? How big a number does a number have to be before it becomes a big number, and not just an oversized little one? (Don’t get the philosophers of mathematics started on this one, by the way.)

They are all rather silly questions, as my more sensible readers will have to concede.

But although words about other words are okay, ideas about other ideas are less easily controlled. I mean, if one’s confession concerned impure thoughts or even lewd imagery, is it sufficient just to prefix them with the purifying image whose linguistic cloaking is (along the lines of) ‘It is not the case that’.

Negation is a problem as well as a solution, and will not let you off very many Hail Marys. Just take it from me – trust an expert for once.

Moreover, to return to the subject of mountains to be ascended, what happens if, thanks to Sigmund Freud, you are hell-bent on climbing a pleasure-gradient on a terrain shaped by your own ideas themselves, and with no idea of how to avoid what geometers call local maximum traps?

I thought that would stop you dead in your tracks, and I was right …

But to return to Collingwood. A crucial objection to a scientific study of the mind, he says, is that it never stays still enough on the petri dish (so to speak) to be studied. If it were just to stop buzzing with ideas, and just stay still for enough time for it to be examined critically, things might be different, but no.

Well, might the same not also be true for the scientific study of the living body, it might be replied? Is human pathology allowed to be a science since everything is perfectly still once necrosis sets in, but ordinary human physiology not?

The counter-response here is that we can at least take still photographs of living physical processes, including brain processes, but what would still shots of mental activity look like?

Hume is sometimes accused of atomising the mind, i.e., of supposing that continuous mental activity could be reduced to a series of unchanging still images in a way that Zeno thought problematic, but which cinematographers nevertheless made possible.

And this leads to yet further complications.

But the weekend slowly approaches, so I shall leave this philosophical investigation on a slightly frivolous note. More startling revelations to come …