Okay, let us get a few things straight first of all.

First, my intellectual background is in the Sciences, not the Arts, more specifically Mathematics and Physics, and not that rather loose ragbag of subjects that form what is generally known as the Humanities (mathematicians just love the implication that they are not human, by the way).

Secondly, I am first and foremost a researcher in my field, and merely teach because it comes with the job. For nearly thirty years, I taught at what used to be called Bolton Institute of Technology (the place now has a University title), and I met some rather unusual students.

I won’t say that the experience was magical, and I am still at a loss to understand how anyone could fancy Ron Weasley‘s mum, though his dad presumably knew differently …

… anyway, not that it is remotely relevant, I shall give you a short movie break now since I know from bitter experience how short an attention span you all have …

Anyway, enough of that.

It is time now to examine John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos more carefully, and to peel away the layers of meaning, (as they say in the Literature departments) and see if a Freudian analysis (or other semiotic devices) can shed light on just what writers and other thinkers have meant by the word telepathy.

First, the plot:

The action is set in the demure, but slightly isolated English village of Midwich. One day, for no apparent reason, all living creatures there fall into a dreamless sleep which lasts for 24 hours. The narrator, to celebrate his wife’s birthday, returns from London to find a road-block just outside the entrance to the village. On inquiring, slightly testily to the man in charge, why he cannot return to his home he is told that nobody can either enter or leave Midwich ‘… and that’s a fact, sir’. On asking again why, he is told (rather ominously) that that is what they are trying to find out. He then has to move his car to one side to let a lorry load of troops move past him towards the village.

Nine months later, all the women capable of giving birth, give birth to a curious set of Children, all with golden hair and golden eyes and apparently genetically identical (remember, this is 1955, and scientific testing is not what it is now). They turn out to have terrifying powers.

The hero of the novel is one Gordon Zellaby, a retired academic of great distinction, who examines the Children in his own way (the authorities have arranged for more pedestrian – and tediously confidential – testing to be set up at the Grange, a disused monastery in the village itself). He quickly discovers that if you teach one of the Boys something all the Boys immediately know it, but not the Girls. It later emerges that the same is also true in reverse: one of the birth-mothers taught her little Girl how to swim, and immediately all the other Girls could swim, but not the Boys. Zellaby duly informs the authorities at the Grange, and notes that they then made further tests of their own, and looked increasingly gloomy thereafter.

In Part II of the novel, the narrator returns with his wife, who along with Mrs Zellaby (who was already pregnant at the time of the Dayout, as it came to be called) was unburdened with exotic offspring, a few years later to find that the Children have developed extraordinarily fast, and that they look like 16 year old teenagers – even though they are only 9 years old. On inquiring, hopefully, how things are in Midwich, Zellaby gravely informs them that the problems have not gone away. On the contrary.

The Children plainly present an existential threat to the entire human race, capitalist or communist, black or white, male or female. We learn, from a member of Military Intelligence, a long-standing friend of the narrator who had persuaded him from the outset to keep discreet tabs on events in Midwich, that there were other groups of Children elsewhere on Earth, and that the last remaining group (found in a small town called Gizhinsk in the Far East of the then Soviet Union) had just been destroyed by a medium-range nuclear missile which the Russians had managed to launch without the Children finding out (their powers diminish with distance). The Children were annihilated, along with the entire town of Gizhinsk (whose human inhabitants they could not evacuate without the Children realizing, of course).

Officially an accident, the Russians nevertheless discreetly alert all the governments of the world to the situation, and urge (sometimes ‘with a touch of pleading‘) that all similar groups of Children be destroyed utterly and immediately.

After ruminating at some length about the ethics of destroying an entire intelligent species, Zellaby decides to take his own life, and that of the Midwich Cuckoos (so called because they hatched in others’ nests), in what we should now call a suicide bombing. The remaining villagers are unharmed.

The novel concludes with a tearful Mrs Zellaby learning, from a letter from her husband, that he had, in any event, only a few months to live. The letter, and the novel, ends with the curt observation that when in the jungle, one must do as the jungle does.

******

So much for the plot: what now about the textual analysis? And, at the risk of allowing philosophy to override literary criticism, we might ask whether we really need the latter (the analysis) since a careful wording of the former (the plot) should suffice. Yes?

Well, perhaps there is a little more to be said. A subtext of the novel concerns the ethics of parental control, and (perhaps?) the inter-generational battle between young and old associated with rock-and-roll and postwar affluence, that was about to begin in earnest.

It is a testament to Wyndham’s literary genius that all these features can be combined into a cosy 1950s thriller, when everything was expected to be normal and highly familiar. The philosopher in me cannot help resist in drawing a comparison between Wyndham and Ryle whose magnum opus, The Concept of Mind (1949), has been said to invoke a picture of Man (in a gender-neutral sense of the word), and the World he inhabits, as something utterly down-to-earth and straightforward, a world of golf, rowing and cricket – without ghosts in machines, or anything disagreeable like that.

Moreover, the novel itself does not reflect all that carefully on the metaphysics of the Children’s mental powers, despite Zellaby‘s lengthy ruminations on the subject. We hear a lot about biology, about the infinite variety of species and the law of the jungle, but the basic physics of brain-to-brain transmission of information is not mentioned at all.

Of course, we are not told what goes on at the Grange, so we may suppose that the relevant tests were made, and that nothing intelligible was found. Hence, the gloomy expressions on the faces of the authorities.

But, on the other hand, if Ryle is right, and mental activity was never something private to its possessor to begin with, telepathy need be no big deal at all, as the half-educated Ritas of this world might put it …

… I can see from the expressions on your faces that it is time for another comfort break. Be thankful that I have not yet talked about underlying metaphors, and other meretricious phrases, and Kate knows what I think about other people’s poetry, as a swift re-reading of my ur-masterpiece will reveal …

… okay, okay, here is your break. But I shall expect you back in 10 minutes …

Anyway, now that you are back and thoroughly refreshed, let us relax the teaching format a little, consider instead a counterfactual novel, where Gordon Zellaby relents and allows the Children to survive and flourish in their own way.

Can we expect to find gangs of blonde hooligans loitering around cash machines (ATMs, if you prefer), trying to guess your PIN number? If so, the immortal phrase ‘I don’t believe it!‘ springs to mind, as a seriously demented Zellaby might put it. (The less said about Mrs Zellaby‘s state of mind, the better.)

I have photographic evidence to back up all my speculations from this nearby possible world, by the way …

How do these beastly young girls, as he calls them, even when Mrs Zellaby is listening in, get away with it, the metaphysician in us all wants to know? I mean, nobody really believes in telepathy, let alone accepts it as a reality, do they?

However, … I just have this rather grainy, but very pretty little photo as evidence, that is all …

and also this musical clip. I am told that the alien language in which it is sung is both Antipodean and may also be heard North of the Border. I suppose this is geographically possible … just …

What exactly do I mean by all this, I hear you all ask with that look of general queasiness you get when, for example, a philosopher of physics starts talking about gender studies?

Well, if you peel away the layers of meaning in your mind (as you do – don’t lie to me), you will get … more layers of meaning.

I mean, like, foundationalism is so yesterday, and although there seems little here to justify the label of coherentism, there are not many other options, are there? Says a voice, from somewhere.

Yes, I too can recognize sarcasm when I hear it, but what did you really mean? Oh.

Well actually, if truth be told, I am glad that I am not having to do all the talking in this class, something which Her Majesty’s Inspectorate warned us about on one occasion, as I recall.

Okay, well, maybe what I am saying now (in case you hadn’t gathered) is that even I can run out of steam and need to recharge my batteries, as a nice mixture of metaphors would have it.

So let us change the subject entirely, and walk down Memory Lane to an event called the Joint Session held in Liverpool back in the beautifully warm summer of 1995, and remember … what, exactly?

(Incidentally, professional philosophers know perfectly well what is meant, in this context, by a joint session even if you don’t, so I should just lose the giggles, if I were you. This is serious).

For who did I find there, at this seriously posh annual gathering (the first I had ever attended, as it happened), but none other than a certain lady whom I had last seen nearly twenty years earlier, but had never forgotten? I should like to say that she remembered me, but here we reach a terrible embarrassment that I can hardly, even now, bear to relate …

… for after a few minutes of small talk whilst I gazed longingly at her visage, she returned the rather terse interrogative sentence ‘Do I know you?‘ … (her very words, which I can remember so vividly as if they had happened only yesterday). OMG, as they say, nowadays.

I laid on the charm, and endeavoured to re-introduce myself, but all I got in return from She Who Must Not Be Named was a Look that would have petrified a Midwich Cuckoo.

Well, I am told that revenge is a dish best served cold, or at least lukewarm, rather like some of those strange things I believe they eat in Japan. One day, I suppose I shall think of a way of Getting My Own Back, but I feel too lacking in self-confidence to try anything now. And not nearly cold-or-lukewarm enough.

In any case, the ur-question is how to arrange the denouement without relying too much on the testimony of others (for I have no intention of meeting up with Her, face-to-face or face-to-anything-else, for that matter, not ever, ever again, no way, José), which I have always thought to be a rather overrated source of knowledge.

Anyway, one thing is for certain and that I need never again fear the so-called death of the author (whatever anyone may wish), given that I now have privileged access, through clever thought-experimentation, to nearby possible worlds where counterpart authors with their counterpart loves may flourish regardless of what may happen in a rather grim part of the North West of England in this rather unprepossessing world.

Still, professionalism requires me to continue my analysis of the text, (or possible text, if you want to modalize everything, as some of us Anglos do). Yes.

But to change the subject entirely yet again, I should personally like to see someone adapt Wyndham’s masterpiece for the theatre. I think that the radio might be a bit too scary, as Orson Welles‘ rendition of the War of the Worlds showed, and rather decisively so.

It would do well at my own nearest establishment, the Bolton Octogan Theatre, and might even be suitable viewing for our local children (with a lower-case ‘c’). I am not sure that anyone would let me convert the text, however, as I have little experience as a playwright.

Metaphysically speaking, I have not quite finished yet. In peering into your minds (and elsewhere, for all you know), I have certainly breached what film-buffs call the fourth wall. In taking liberties with intertextuality, as lit. crit. types all it, I shall soon breach a fifth, and contemplate how, with nothing more than a subtle knife, I can cause all of Heaven’s dark materials to leak in my direction.

As you do, when you feel in the relevant mood, and the irresponsible hooliganism of adolescence re-enters one’s weary frame.

So what next, I hear you ask nervously, wondering just whether there might be another class scheduled for this seminar room? Well this, for example.

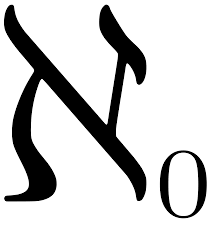

Mathematical induction (don’t ask) was always something of which I was a big fan, and for every N there is always an N+1, so how many more walls are there to tear down? As a trained mathematical logician, I am personally acquainted with what we-in-the-know call the transfinite hierarchy, and know (unlike you, for example) that an inaccessible cardinal is not a dodgy character from Father Ted.

So don’t bother looking at this next film, if I were you, as it won’t affect me in the least. (In any event, you have to wait until towards the very end to see the bit I keep thinking about. As you possibly already know …)

Now, as I was saying, I am talking about Midwich Cuckoos, and am also talking about alien consciousness, so how can I fail to ask what it is like actually to be a cuckoo of the relevant kind?

Well, there are advantages, of course, notably hair and eye-colour to die for, and a certain ability to influence people (though making friends proves to be less easily achieved).

Alien solidarity is a bit like human solidarity raised to the power ten, so much so that it can seem as if there are only two Individuals involved: the Boy and the Girl

(or Adam and Eve, as our original hero, Gordon Zellaby muttered to himself darkly).

Dangerously attractive, yes? But also alone, and very far from home.

Liverpool (and even Japan) can seem alien to an Englishman in New York, and there is so much about the cuckoo-world that we shall never, ever know.

Fortunately, I happen to know – for a fact – their taste in music.

Enough said, I think.